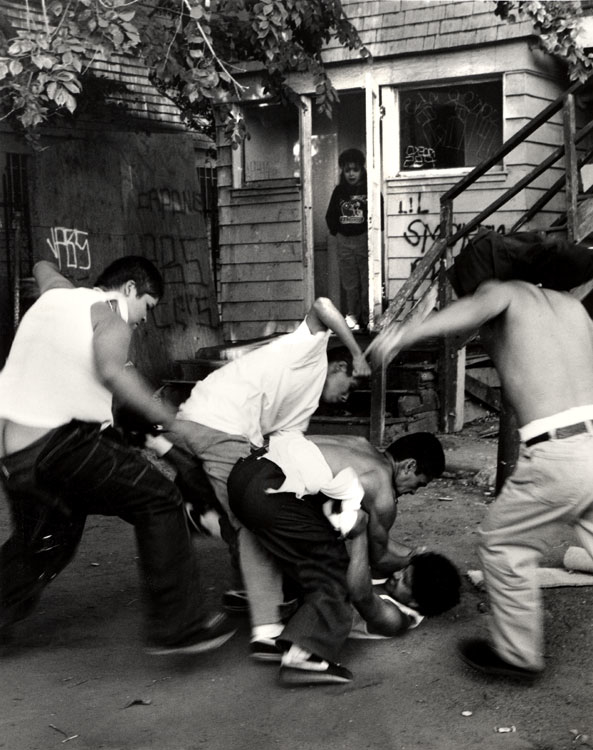

The

country has fought for decades to stop gang violence. We have tried many

methods to stop it. In some places, gang-related crime rates have dropped after

the government introduced some methods to address gang violence. However, is gang

violence actually disappearing in the country? The answer is, no. Gangs still

exist and gang violence still exist. We can only reduce the gang violence. We

cannot stop gang violence because all methods to address gang violence have

their weaknesses which cannot solve the problem completely.

Even

though problem-oriented policing can reduce gang violence, it cannot make sure

the gangs are going to stop. In the book Don’t

Shoot, by David Kennedy, who uses problem-oriented policing as a base and

promotes the project “Operation Ceasefire” to fix the trouble communities, shares

his journey about stopping gang violence. According to Kennedy,

problem-oriented policing is basically solving problems by “picking a problem,

researching it, finding partners, and figuring out a way to fix it” (31).

Writing about the success of problem-oriented policing, Kennedy proves that

Operation Ceasefire works as a method to reduce gang violence. For example, he

promotes Operation Ceasefire High Point, a place that is suffering from serious

gang problem. After Kennedy’s team had worked on it, Kennedy states that,

“there hasn’t been a homicide, a shooting, or a reported rape in the West End

since May 18, 2004. It’s been six and a half years, as I write this. The

community has its streets back. People started going outside, using the parks,

fixing up their houses” (183). Kennedy believes that problem-oriented policing

is really useful to stop gang violence. It can completely break down the gang

and give the streets back to the community. However, determining whether problem-oriented

policing works or not, it is really based on the gangs themselves. Therefore,

if the gangs are not willing to compromise, problem-oriented policing will not

work. The people who work with problem-oriented policing do not recommend using

law enforcement to lock people up. They believe solving the root causes of the

problem is the only way to stop gang violence. Kennedy states that “there was

no conceivable way to do so with ordinary law enforcement, no way to crack the

one-in-fifteen-thousand program. But it could be done another way: get a drug

case ready to go, and then don’t arrest the dealer. Tell him that if he starts

selling again the case would be activated and he’d be picked up, without any

new investigation or a single bit of new evidence.” (160) Kennedy tells the

police not to arrest the drug dealers even if they have all the evidences which

prove they are breaking the law. He believes that gang members will listen and

make the right choices to stop making mistakes. Thus, the choices are on the

gang members’ hands; they can pick to continue what they are doing and take the

risk to be sent to the jail or get off from the streets. However, sometimes to

stop or not to stop may not be the gang members’ choice. In

The Dream Shattered, Patrick Du Phuoc

Long, who is a Vietnamese counselor trying to help the Indochinese youths,

discusses the reasons of Indochinese children staying in gangs. Long explains

that in the gangs, there are the people called “Big Brother” who control the

younger members. He states that “the Big Brother’s

greatest skill lies in his ability to create a fanatical loyalty in the younger

members who come under his spell. As he initiates his young charges into the

world of crime, the Big Brother orders them to deny any knowledge of him in the

event that the group is caught engaged in criminal activity” (107). According

to the “Big Brother rule”, the younger gang members are always those who are

committing crimes on the streets for the Big Brother. They are loyal to the Big

Brother; hence, they think that it is a glory to do something for the Big

Brother. They have no choice but continue committing crimes and drugs dealing. Even

if the younger gang members are arrested, there are other gang members to do

their jobs. As a result, we can never stop gang violence with this. It is clear

that problem-oriented policing do not work everywhere and there’s no way to

make sure if it will work because it’s based on the gang members.

Besides

problem-oriented policing, the court uses gang injunctions to stop gang

violence. Even though gang injunctions can stop gangs from hanging out in the

public, they do not help the gang members to get a new life. So they will find

other ways, which can be illegal, to live their life. Gang injunctions are

court orders restricting targeted gang members’ activities to avoid their

chances involving in gang-related crimes. In the article “Oakland’s Gang

Injunction Is a Chance to Save Lives”, the authors, John Russo and Anthony

Batts explains that gang injunctions are effective because “it would prevent

them from hanging out together in public and from being on the street between

10 p.m. and 5 p.m. When members of the gang are caught committing crimes they

are often together, and it is often during late night hours” (1). Russo and

Batts believe that the gang members are all forced to stay home and there will

be no more gang violence; this is only possible for a small group of gangs.

However, in this modern society, the gang members can still keep in touch with

the gangs even if they are restricted to stay out of the street. For example,

online network is a really good source to keep in touch with gang-related

crimes. In the article “The War on Gangs”, the author Alex Kingsbury states

that “wherever they

operate, gangs are increasingly turning to computers and the Internet. Often

behind password-protected sites, they post photo-graphs of their own gang signs,

colors, and tattoos. Police even report that some gangs are using their

websites to take positions on local political issues” (n.pag.). Kingsbury explains how the gang members can still

involve in gangs. Therefore, gang injunctions can only get the gang members

“out of the streets” but do not truly get them out of the gang. Moreover, the

targeted gang members’ activities are restricted but with the online network,

they can get new members to commit crimes for them. The gang injunctions do not

solve the root causes and stop the gangs from reforming. On the other hand, there is an “opt-out” system that can let the

targeted gang members who have turned their life around to get removed from the

injunction list. However, the procedures are very complicated which they may

have to be restricted for their whole life. In the article, “No Way Out: An Analysis of Exit Process of GangInjunctions”, from California Law Review,

the author Lindsay Crawford investigates the process of “opt-out”. Crawford

states that “community

members and local leaders inquired further, asking whether former gang members

had any success removing their names from injunctions. The answer was

startling: in the entire history of the Los Angeles experience with civil gang

injunctions, no gang member had ever successfully removed his or her name from

an injunction” (162). Crawford explains that only Los Angeles and San Francisco

provide an unofficial way to get removed from the list. In other words, for

most of the places that only provide the official “opt-out”, the gang members

are not going to be removed even they have turned their life around already. In

the article “Gang Injunctions: Fact Sheet from the ACLU of Northern

California”, ACLU claims that since there are no way for the gang members to

get back to the normal life without being labeled as gang members, “the

injunction could follow them the rest of their life, which can make it more

difficult to avoid gang activity.” (1) ACLU believes that the government is

giving no way out for the gang members are just going to push them back to the

street life or in another form to be in gangs. The gang members need to make

money for life; therefore, being in gangs and committing crimes may be the only

way that they can live their life. Therefore, instead of forcing the gang

members out from the street, the government should solve the root causes which

truly get them out of the gangs.

In the meantime, to solve the root

causes of gang violence, the government provides other methods. Even though

social services can help the gang members with job and education

opportunities, not all the gang members who wanted to turn their life around

can receive help. Writing about the success of social services, ACLU states

that “Los Angeles has numerous gang injunctions – more than any other city, yet

lost more than 10,000 youth to gang violence in the last 20 years. New York is

a major city with the potential for serious gang problems, yet in 2005 Los

Angeles had more than 11,000 gang-related crimes, while New York faced 520.

What has been shown to work at reducing violence and gang activity is funding

social services” (1). ACLU provides the data that New York, where works on

funding social service rather than gang injunctions, is being more successful

than Los Angeles in reducing gang violence. When the gang members get jobs,

they don’t have to stay on the street all the time; they can actually get out

of the gangs. However, not every single gang members can receive help from the

social services. For example, “call-in” is one of the programs that gather the

gang members in a room and notice them they can provide job and education

opportunities. Kennedy also participates in setting up a call-in. The Operation

Ceasefire team sends letters to the gang members to invite them to the call-in;

however, he states that “we didn’t know if anybody would show up. Probationers

and parolees ignore their terms and conditions all the time and hardly anything

ever happens to them.”(63) The team’s jobs are just sending out letters and

wait for gang members to come to the meeting; hence, there is a possibility

that no one will show up. They are at a passive position where not all the gang

members can receive the messages to stop gang violence and receive help. In

addition, Ali Winston, the author of “Proposed Oakland Gang Injunctions May

Complicate Anti-Gang Efforts”, states that “City documents indicate call-ins

have suffered from a perception that the program is a set-up to being put on an

injunction list” (1). Winston explains gang members may not show up to the

call-in because they are scared that it is a set up; in other words, the gang

members think that if they show up to the call-in, it means that they admit

they are gang members and get arrested. As a result, gang violence cannot be

stop because the gang members do not trust the government is actually being

here to help; the gang members are just going to stay in where they are and

keep involving in gang violence.

Last, prevention

program can prevent future gang members from forming; even though prevention

programs can prevent kids from joining gangs, it takes too long that the

current problems are not solved. Long

interviews one of the Indochinese high school students observes that “we have

been treated like outsiders. We haven’t been accepted by the American culture.

Gangs allow us to identify with something” (qtd. in Long 100). According to the

high school student, providing more care and help to the students to stay in

school is necessary. The government should fix the education system and put the

students into the class level which is suitable for them. School should work on

accepting the students who are the minority groups; therefore, they are not

going to drop out of school due to the failure in classes and losing connection

to the school. However, discussing the effectiveness of prevention program in

education, Kennedy states that “let’s say it’ll take fifteen years to

completely retool the public schools so they work for the most disadvantaged

kids in our most disadvantaged communities: wildly optimistic, but let’s say.

Let’s say it’ll take another fifteen years to get the first wave of kids

through the new schools so they hit their years of peak risk immunized to the

violence. That means we live with all this for another three decades. At best” (212).

Kennedy explains that to fix the education system is going to take too long

that we should work on solving the current gang violence problem. Taking

fifteen years to stop the gang violence is not worthy; instead, using the other

methods to stop the current gang violence is even better. Meanwhile, there are

afterschool program to keep the kids out of gangs. However, in

Always Running, Luis J. Rodriguez,

who was a former gangster in L.A., claims that it’s not as

easy to get out of the gang because of peer pressure; he states that “I thought

about the globe. Chente was right. A bigger world awaited me. But I also knew:

Once you’re in Las Lomas, you never get out – unless you’re dead.” (236) Chente,

who is the “teacher” among the Mexican study group, tries to get Rodriguez out

of the gang. Rodriguez knows that he should live a normal life but his friends

are all in gangs, thus he can’t leave the gang or he is betraying his friends.

In other words, even though there are prevention program for the students,

other than the problem – it takes too long to see the result, it also base on

the kids’ choices.

The

government is thinking as many methods as they could think of to stop the gang

violence; however, there isn’t a perfect method which can stop gang violence

completely. Gangs are still going to exist in the community. We have to live

with the gangs. Nevertheless, reducing the gang violence to a point where we

can live comfortable with it is possible. We have to work with the government,

trusting the government to help fighting with gang violence. Consequently, it

is not going to be a problem that threatening our safety in the community.

Works Cited

Kennedy,

David M. Don’t Shoot. One Man, A Street

Fellowship, and The End of Violence in

Inner-City

America.

New York: Bloomsbury USA, 2011. Print.

Kingsbury,

Alex. “The War on Gangs.” U.S. News & World Report 145. 13 (2008): 33-36.

EBSCOhost.

Web. 1 Dec. 2012.

No comments:

Post a Comment